Within

The Body in the Mirror: Shapes of History in Italian Cinema (1992) Angela Dalle Vacche endeavours to illuminate the national-specific aspects of Italian cinema, relating them to the distinctive historicist orientation of the country's intellectual and cultural life over the course of the 20th century.

Her analysis begins further back in time, however, with Renaissance art, although unusually she does not focus on the discovery of perspective in apparatus theory terms (basically that by replicating quattrocento perspective, the film camera and cinema more generally cannot but also replicate the humanistic worldview embedded within it) but instead emphasises its legacy in other arts:

"From painting to the cinema, body, spectacle and allegory are the three parameters that control how Italian filmmakers depict the national identity and adjust their vision of contemporary life within the these parametric forms. Allegory, spectacle, and body not only characterize Italian Renaissance painting, but influence two art forms that in themselves are important to Italian cinema: opera and the commedia dell'arte.” (4)

Whereas opera focussed on the large scale / spectacular, the commedia dell'arte focussed on the small scale / intimate. Both, however, could still be contrasted with the literary in terms of their universal appeal within an Italy - not yet an Italy "in itself" let alone "for itself", if we can appropriate from Marx's class analysis to a nation based one - divided by region and language even beyond unification in the latter half of the 19th century and then increasingly by class over the course of the 20th.

While the nationalist and fascist projects over the years certainly constructed a more unitary Italian identity through the education system, military service and the mass media, the search for something with sufficiently broad appeal nevertheless remains a hallmark of the Italian cinema.

Consider - for instance - the divergent characteristics of the

prima and

terza visione circuits and audiences as discussed by Christopher Wagstaff. This, in turn, cannot but affect the type of cinema that is made, what it emphasises and downplays. In this regard Argento is fortunate: having begun his career as a writer and only turning his hand to direction out of fear of what another would do to his

The Bird with the Crystal Plumage script, he turned out to have a visual flair. In a similar vein his oft-criticised writing could also be read as a symptom of his nationality and the enduring legacy of the

questione della lingua. (Here it is perhaps also worth recalling the frequent failures of language in Argento's cinema, whether the problems the Roman Romolo and Milanese Cainazzo have communicating with one another in

Le Cinque giornate in the absence of a completely common

lingua, or musicology student Mark Elliot in

Inferno being mistaken for a professor of toxicology - perhaps intentionally; the misreading is after all made by the incognito Mother of Darkness.)

Another aspect of Dalle Vacche's discussion here which is relevant is that of the

maschere or mask, one of the three key elements of the aforementioned commedia dell'arte alongside pantomime and improvisation. Within the commedia, the role of the mask was to identify particular character types to the audience - i.e. while concealing the identity of the performer, the mask also made the nature of the role he was playing immediately recognisable. This, I think, is highly significant when we turn to the featureless stocking mask of the archetypal giallo killer, as epitomised by Bava's

Blood and Black Lace and later codified in the plethora of imitations that followed in the wake of

The Bird with the Crystal Plumage's phenomenal box-office success.

For while this mask may identify its wearer qua killer, at least diegetically, it also conceals his or her underlying identity. Anyone could turn out to be the killer when typification fails. Indeed, is is worth remembering how in

Blood and Black Lace Max Morlachi has Countess Como don the mask and other accoutrements to commit a murder while he is in police custody in order to equip him with an ironclad alibi, or how in

The Bird with the Crystal Plumage Alberto Ranieri does his best to throw the police off his murderous wife's trail by doubling for her and assuming her killer identity himself. In cases like these, then, the masked killer cannot even be pinned down to a single identity. If not quite legion, s/he (and here remembering that, via her misidentification with her attacker, Monica Ranieri could be argued, like many of Argento's characters, to be suffering from a degree of gender confusion) is at least doubled/multiple.

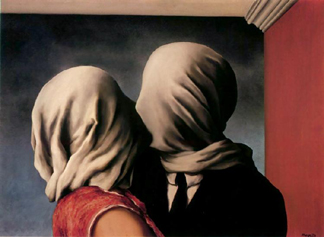

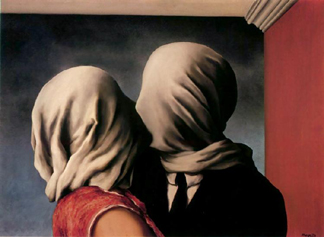

Another thing worth mentioning here is the more painterly heritage behind the giallo killer's mask. Though often most readily associated with the Belgian Surrealist Rene Magritte, in works such as

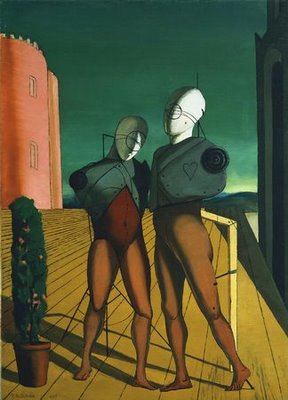

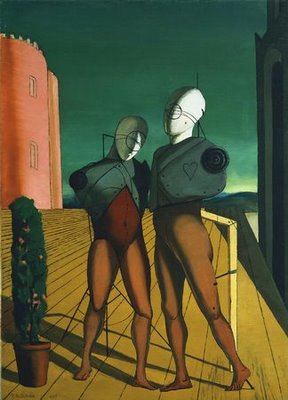

The Lovers, a specifically Italian reference point can also be identified in Giorgio de Chirico's

pittura metafisica / metaphysical painting, within which blank-faced mannequins are a recurrent feature. (We can also think here of the original credits sequence to

Blood and Black Lace, where the characters, many of their number the

sei donne per l'assassino, are introduced alongside mannequins.)

Magritte's

The Lovers

De Chirico's

The Two SistersWhile Dalle Vacche does not refer to Argento within either

The Body in the Mirror or her later

Cinema and Painting: How Art is Used in Film (1997) a line of influence can nevertheless be traced from De Chirico to Michelangelo Antonioni to Argento. Discussing Antononi's

The Red Desert in the latter study, Dalle Vacche notes that "de Chirico's puppetlike intruders in his airless piazze are nothing but the other side of F T Marinetti's mechanical man, whose direct descendant we encounter in the toy robot moving up and down Valerio's room and interrupting Giulia's natural sleep," thereby reminding us - to give only the most obvious example - of the mechanical doll in

Deep Red with which Martha terrorises Professor Giordani before murdering him.